Working in an Uptown basement, Dr. Newton K. Wesley helped craft a solution to his deteriorating vision: Comfortable contact lenses that could be worn for long periods. Considered a pioneer in the contact lens industry, the Chicago-based Dr. Wesley went on to become one of the leading developers and manufacturers of contact lenses, paving the way for the modern contacts we know today.

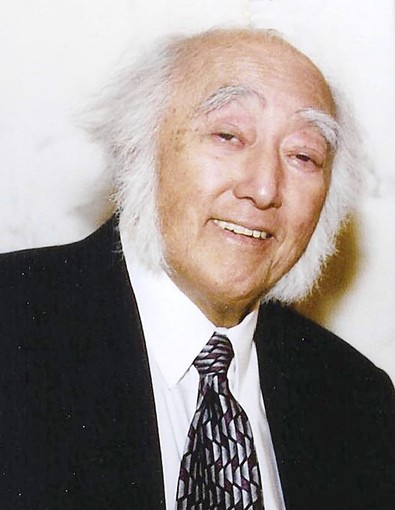

Dr. Wesley, 93, died of congestive heart failure on Thursday, July 21, at the Stephenson Nursing Center in Freeport, Ill., said his son Roy. Born Newton Uyesugi to Japanese-immigrant parents in Westport, Ore., Dr. Wesley thrived in school and managed to graduate from high school at 16. By 22, he had an optometry practice in Portland, Ore. He had also begun to operate his alma mater, what is known now as Pacific University College of Optometry, Roy Wesley said. But in 1942, a year after he married the late Cecilia Sasaki Wesley, the optometrist and his family — including two young children — were sent to the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho, Roy Wesley said. Dr. Wesley, who for business purposes Anglicized his name to what he thought sounded similar to his Japanese last name, was able to receive permission to leave the camp — though his family stayed, Roy Wesley said.

The optometrist moved to the Midwest and attended Earlham College in Indiana, then settled in Chicago. When his family was released from the camp at the end of the war, they joined him in Uptown, Roy Wesley said.

It was in Uptown that Dr. Wesley began researching a solution to his vision problems. The optometrist suffered from keratoconus, a degenerative disease of the cornea that affects vision, and had been told by experts that he’d likely lose his sight, his son said.

He knew that contact lenses helped him see, but the lenses available in the 1940s couldn’t be worn for long periods. So Dr. Wesley and his partner, George Jessen, began to research and develop a new type. Wesley and Jessen eventually developed the plastic lenses known as rigid contact lenses. The lens fit over just the cornea, unlike its predecessor, which also rested on the sclera (the white area), said Neil Hodur, a professor at the Illinois College of Optometry and a colleague and friend of Dr. Wesley’s.

The end product was lenses that were smaller, thinner and longer-wearing, said Alfred Rosenbloom, a former dean and president of the Illinois College of Optometry. “That’s actually what saved his own vision,” Roy Wesley said.

In 1946, Dr. Wesley and Jessen formed the Plastic Contact Lens Co., which later became Wesley-Jessen Inc.. It was acquired in 2000 by Ciba Vision.

Dr. Wesley’s company began to manufacture and distribute the new, more comfortable lens, though it took an aggressive marketing campaign to convince the 1950s public that placing the lens in the eye was safe, Hodur said. He also founded the now defunct National Eye Research Foundation.

Dr. Wesley, known for his bushy sideburns, toured the country marketing and promoting the lenses to eye care professionals, celebrities like Phyllis Diller and television audiences — who were wowed by his model, Leo, the contact-wearing rabbit. The optometrist traveled so often that he learned to pilot a plane that took off from Meigs Field.

Dr. Wesley’s family also says that in the 1950s, he campaigned to get “contact lens” into the dictionary.

“He’s one of the people we can thank for where we are now in contact lenses,” Hodur said. In addition to his son, Dr. Wesley is survived by his wife, Sandra; three daughters, Shona, Justine and Jenna Williams; three other sons, Morgan, Taylor and Newton Lee; five grandchildren; and three great-grand children.